“It was a difficult situation. You’re working in a crowded area with multiple different types of factors going on: there’s traffic around, there’s people on the street, … and we had another patient on the scene, also, who identified themselves as needing help,” said Dave Leary, a spokesman for the Ambulance Paramedics of B.C., who was one of the paramedics on the call.

“The stress levels are high.”

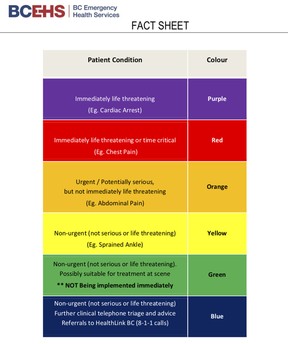

This situation was deemed a Code Purple, the most serious designation given by ambulance dispatchers for life-threatening calls. B.C. Emergency Health Services, which oversees ambulances, uses a six-colour scale to determine which calls should receive high-priority response times, with Code Reds — “immediately life-threatening or time critical” — being the second-most serious.

These purple and red calls have steadily increased over the last three years in B.C., according to new data provided to Postmedia. It’s yet another factor that’s putting extra strain on an already-ailing health care system that has seen hospital emergency rooms temporarily close due to severe shortages of nurses and other health care workers.

And when these very sick patients are brought by ambulance to hospitals, which are increasingly overcrowded and under-resourced, they require urgent attention from doctors and nurses.

“We’re seeing very significant increases in purple and red calls, and all of those end up in the emergency room,” Health Minister Adrian Dix told Postmedia recently. “So our staffing (in ERs) is not just affected quantitatively but qualitatively right now.”

Purples and reds represented 31 per cent of all ambulance calls in 2019/2020, and rose to 34 per cent by 2021/2022. There were 14,169 purple calls and 144,773 red calls in the most recent fiscal year.

The health ministry has boosted funding for B.C.’s overwhelmed ambulance service. While the Ambulance Paramedics of B.C., the union representing these workers, appreciates the government’s new investments, it argues the province is still short 1,000 paramedics; roughly half of them are needed in urban centres and the rest in rural communities, said president Troy Clifford.

This has led, on some days, to as many as 30 per cent of rigs going unstaffed and some rural communities temporarily having no local ambulances, union leaders say.

On July 17, for example, an Ashcroft woman who lives in the same block as the local hospital, which was closed at the time due to short staffing, died after she went into cardiac arrest and the closest ambulance was nearly 30 minutes away.

The Ashcroft call was categorized as serious by dispatchers, but the shortage of paramedics makes handling even the purple and red calls a real challenge.

“Purples are immediately life threatening, like cardiac arrest, respiratory arrest, full obstruction choking. … Reds are the next down, which are cardiac chest pain, severe shortness of breath, partial obstruction of an airway, severe bleeding, unconscious patients,” said Leary, a 23-year paramedic in Surrey and Delta, who spoke to Postmedia on behalf of his union.

“They can be the most challenging calls and they are the ones that take up a great amount of resources. … Once you transport them to a facility, like an emergency room, it ends up that utilizes the majority of their resources that are on shift also.”

While purple and red calls are on the rise, so too are less urgent calls.

B.C. Emergency Health Services (BCEHS) stats show ambulance calls steadily climbed from 2016 to 2019, dipped slightly in 2020 during pandemic restrictions, and then rose again in 2021 — with an average of more than 1,500 calls every day. The union says 2021 was the busiest year on record.

And 2022 appears to be even busier. Call volumes spiked on some days this year to between 1,700 and 2,000, Clifford said.

E-Comm, B.C.’s emergency communications centre, predicted this year would see a 12 per cent increase in all 911 calls (including police, fire and ambulance), compared to 2021. “We’re seeing some of the highest emergency call volumes we’ve experienced in our 23 years of service,” E-Comm spokeswoman Jasmine Bradley said in June.

Reasons for increased demand for ambulances include the overdose crisis, more people testing positive for COVID-19, a growing and aging population, mental health challenges, the shortage of family doctors, extreme weather events, and busier highways as people go on postponed vacations. Overdoses alone were responsible for nearly 100 calls a day for paramedics in 2021, a new record.

“We’re doing a lot more calls, and a lot more and more serious … And then this spring, it just seems to have really taken off,” said Clifford, a paramedic in Osoyoos, who recently attended a life-threatening call for an overdose victim whose terrified mother was performing first aid when the ambulance arrived.

“(Purples and reds) are the highest of the highest of acute calls. So (BCEHS) have reported that those numbers went up but, overall, all our calls went up.”

The health ministry, in a statement, did not address the union’s claims that B.C. is short 1,000 paramedics, or that as many as one third of ambulances can sit unstaffed.

Instead, the ministry said it boosted the ambulance budget from $424 million in 2017, when the NDP was elected, to $559 million this fiscal year. Since 2021, when the service melted down amidst a spike in calls during the heat dome, 500 new full-time and part-time paramedic positions were added in rural and remote areas, and at least 125 in urban areas, although it’s not clear from the ministry’s statement if those positions have all been filled.

The ministry also added 42 new dispatch positions and 22 new ambulances — nine of which are on the road, while the rest are to arrive by the end of this year, the statement said.

To support paramedics, the ministry said, it has a new process that deploys staff more quickly when there are “dramatic spikes in demand.”

“I honestly believe in my heart that the government is making an effort,” said Ian Tait, a regional vice-president with the union. “I believe senior leadership is making an effort. Do I think it’s a little bit too late? Yes, I think they should have been on this years ago.

“The numbers of recruits over the last two years have been nowhere near even keeping up with the amount of retirees. … The government, for their part, they’ve added ambulances all over the province. The problem is there’s not physically enough human beings to get behind the wheel of those ambulances.”

As a result, British Columbians are bearing the brunt. An 85-year-old Langley woman waited 2 1/2 hours for an ambulance in “excruciating pain” on July 18, according to a Tweet from her daughter-in-law. A 91-year-old Chilliwack woman also waited 2 1/2 hours for an ambulance in January, her grandson posted on social media.

Joseph Sikora, founder of Ground Zero Ministries, which provides outreach to Abbotsford’s homeless population, has witnessed people in distress on the street, due to either poisoned drugs or extreme heat, wait 30 minutes for medical aid to arrive.

The ministry acknowledges response times are up, but says it has made efforts to try to reduce them. Last month, responses for the highest priority calls met the target in urban areas of under nine minutes, the statement said, but added: “However, the median response times have increased slightly for purple- and red-coded patient events.”

The ambulance service is creating new measures to help patients with less serious injuries in an effort to reduce the strain on paramedics and emergency rooms.

The dearth of paramedics led to Clifford’s community of Osoyoos going without an ambulance one day recently, a dilemma that’s been repeated in other places like Quesnel, Kitwanga, Agassi and Boston Bar, union leaders say. Even in urban areas, there was recently a shortage of ambulances in Vancouver, and response times have grown in areas such as Burnaby and the Fraser Valley.

“Last weekend, our staffing was absolutely decimated all weekend long. … It was catastrophic,” said Tait, who works in Chilliwack and has extra training to attend the most serious calls as an advanced life support paramedic.

Like with nurses, the paramedic shortage, caused in part by the burnout of existing staff and challenges to hire new staff, is not just happening in B.C. but across Canada.

Some of the solutions to attract more recruits, according to the union, are to increase paramedics’ wages so they are on par with police and firefighters, and to eliminate the on-call model in rural communities.

Union officials say this is a great career and that paramedics love helping people, but a significant number of workers are off because of the stress and mental fatigue from the growing number of calls and the shrinking workforce.

“We’re seeing incredible amounts of psychological injuries, the PTSD, the … fatigue, you can’t run at those levels and not have impacts on your well-being,” said Clifford, a paramedic for 34 years.

And 911 calls could be reduced — everything from the high-urgency code reds to the low-urgency code blues — if the other parts of the health care system were improved, including better access to family doctors and proper mental health and addictions care, he said.

“There’s a lot of people that are in the community that end up defaulting to the 911 emergency system, which we know is not the best place for opiate addiction, or mental health issues, unless they’re having an immediate crisis. And, unfortunately, in many communities, that’s where they get into the emergency system,” said Clifford.

“There’s a lot of solutions that I think a lot of people are working on. But … people expect to have an ambulance in their time of emergency, and a timely ambulance to treat and transport to the hospital. And that’s absolutely what we have to get to. And we’re not there right now.”