A tidal wave of chronic illness could leave millions of people incrementally worse off.

In late summer 2021, during the Delta wave of the coronavirus pandemic, the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation issued a disturbing wake-up call: According to its calculations, more than 11 million Americans were already experiencing long COVID. The academy’s dashboard has been updated daily ever since, and now pegs that number at 25 million.

Even this may be a major undercount. The dashboard calculation assumes that 30 percent of COVID patients will develop lasting symptoms, then applies that rate to the 85 million confirmed cases on the books. Many infections are not reported, though, and blood antibody tests suggest that 187 million Americans had gotten the virus by February 2022. (Many more have been infected since.) If the same proportion of chronic illness holds, the country should now have at least 56 million long-COVID patients. That’s one for every six Americans.

So much about long COVID remains mysterious: The condition is hard to study, difficult to predict, and variously defined to include a disorienting range and severity of symptoms. But the numbers above imply ubiquity—a new plait in the fabric of society. As many as 50 million Americans are lactose intolerant. A similar number have acne, allergies, hearing loss, or chronic pain. Think of all the people you know personally who experience one of these conditions. Now consider what it would mean for a similar number to have long COVID: Instead of having blemishes, a runny nose, or soy milk in the fridge, they might have difficulty breathing, overwhelming fatigue, or deadly blood clots. Even if that 30 percent estimate is too high—even if the true rate at which people develop post-acute symptoms were more like 10 or 5 or even 2 percent, as other research suggests—the total number of patients would still be staggering, many millions nationwide. As experts and advocates have observed, the emergence of long COVID would best be understood as a “mass disabling event” of historic proportions, with the health-care system struggling to absorb an influx of infirmity, and economic growth blunted for years to come.

Indeed, if—as these numbers suggest—one in six Americans already has long COVID, then a tidal wave of suffering should be crashing down at this very moment, all around us. Yet while we know a lot about COVID’s lasting toll on individuals, through clearly documented accounts of its life-altering effects, the aggregate damage from this wave of chronic illness across the population remains largely unseen. Why is that?

A natural place to look for a mass disabling event would be in official disability claims—the applications made to the federal government in hopes of getting financial support and access to health insurance. Have those gone up in the age of long COVID?

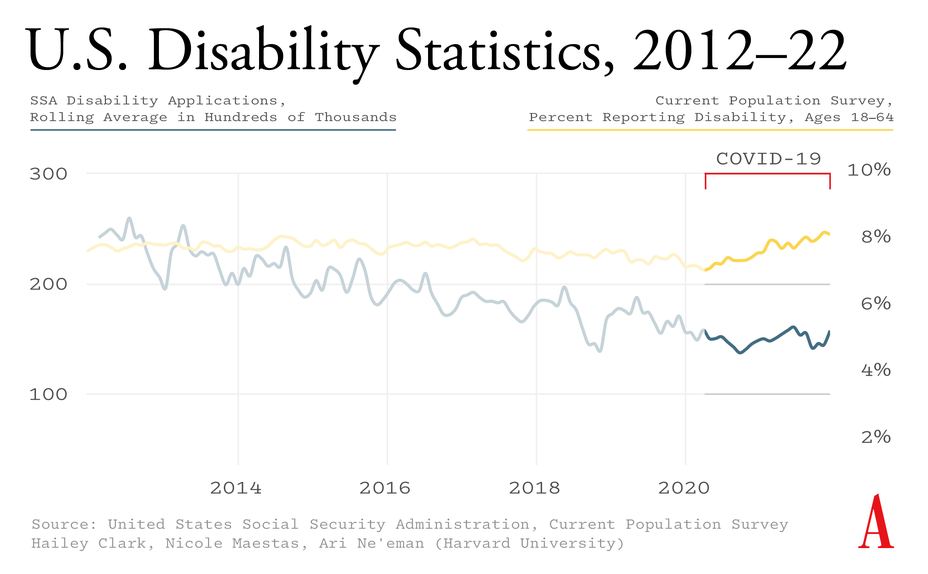

In 2010, field offices for the Social Security Administration received close to 3 million applications for disability assistance. The number dropped off at a steady rate in the years that followed, as the population of working-age adults declined and the economy improved after the Great Recession, down to just about 2 million in 2019. Then came COVID. In 2020 and 2021, one-third of all Americans became infected with SARS-CoV-2, and a significant portion of those people developed chronic symptoms. Yet the number of applications for disability benefits did not increase. In fact, since the start of the pandemic, disability claims have dropped by 10 percent overall, a rate of decline that matches up almost exactly with the one present throughout the 2010s.

“You see absolutely no reaction at all to the COVID crisis,” Nicole Maestas, an associate professor of health-care policy at Harvard, told me. She and other economists have been looking for signs of the pandemic’s effect on disability applications. At first, they expected to see an abrupt U-turn in the number of applications after the economy buckled in March 2020—just as had happened in the aftermath of prior recessions—and then perhaps a slower, continuous rise as the toll of long COVID became apparent. But so far, the data haven’t borne this out.

That doesn’t mean that the mass disabling event never happened. Social Security field offices were closed for two years, from March 17, 2020, to April 7, 2022; as a result, all applications for disability benefits had to be done online or by phone. That alone could explain why some claims haven’t yet been filed, Maestas told me. When field offices close, potential applicants have less support available to help them complete paperwork, and some give up. Even now, with many federal offices having reopened, long-haulers may be struggling more than other applicants to navigate a bureaucratic process that lasts months. Long COVID has little historical precedent and no diagnostic test, yet patients must build up enough medical documentation to prove that they are likely to remain impaired for at least a year.

In light of all these challenges, federal disability claims could end up as a lagging indicator of long COVID’s toll, in the same way that COVID hospitalizations and deaths show up only weeks after infections surge. Yet the numbers we have so far don’t really fit that explanation. The Social Security Administration told me last week that the federal government had received a total of 28,800 disability claims since the start of the pandemic that make any mention whatsoever of the applicant having been sick with COVID. This amounts to just 1 percent of the applications received during that time, by the government’s calculation, and would represent an even tinier sliver of the total number of long-COVID cases estimated overall. When I passed along this information to Maestas, she seemed at a loss for words. After a pause, she said: “It’s just not a mass disabling event from that perspective.”

The National Health Interview Survey provides another perspective, though the population effects of long COVID are no easier to find in those data. The survey, performed annually by the federal government, measures disability rates among Americans by asking whether they have, at minimum, “a lot of difficulty” completing any of a set of basic tasks, which include concentrating, remembering, walking, and climbing stairs. The proportion of people who reported such difficulties was flat through 2021: 9.6 percent of adults were disabled in December 2019, as compared with 9.5 percent two years later.

Other sources of disability data do hint—but only hint—at long COVID’s consequences. When the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics performs its monthly employment survey, it asks Americans a few basic questions about their physical and cognitive health, including whether they have difficulties concentrating, making decisions, walking, or running errands. By this measure, the number of people reporting such problems began to nudge upward by the middle of 2021. (Disability rates briefly appeared to decline at the start of the pandemic, when in-person interviewing went on hold.) But this increase, from about 7.5 to 8 percent of the working-age population, represents a tiny blip compared with the extrapolated number of Americans who have long COVID, and most of this new cohort is still able to work. Maestas suspects that these particular disability numbers represent the first sign of a true upswing. “As you watch them keep going up each quarter, it’s starting to look like maybe there is something going on,” she said.

The survey measures described above may be affected slightly by the pandemic’s disproportionate death toll among already disabled people. They could also only ever tell one part of the story. At best, they’ll capture a certain kind of long COVID—the sort that leads to brain fog, fatigue, and weakness, among other severe impairments in memory, concentration, and mobility. One of the overarching problems here is that long COVID has been associated with many other ailments, too, such as internal tremors, sudden heart palpitations, and severe allergic reactions. None of these issues is likely to show up in the NHIS or BLS data, let alone qualify someone for long-term financial support from the Social Security Administration.

If the “mass disabling event” plays out as tens of millions of cases of shooting nerve pain or diarrhea, for example, or even just a persistent loss of smell, then you might never see a large jump in the number of Americans who report having difficulty functioning. In that case, though, more Americans might end up seeking out their doctors for evaluations, tests, and treatments. A growing number of symptoms, overall, should lead to a growing burden, overall, on the country’s health-care system.

The available data suggest that the opposite is true, at least for now. A report from Kaiser Family Foundation, released last fall, found that both outpatient and inpatient health-care spending was actually lower than projected through the first half of 2021—even accounting for millions of acutely ill COVID patients. “We have not seen pent-up demand from delayed or forgone care,” the nonprofit wrote. (This modest spending was recorded despite the fact that the proportion of Americans with health insurance increased during the first two years of the pandemic.) In February, the consulting firm McKinsey surveyed leaders from 101 hospitals around the country, who said that outpatient visits and surgeries were still below pre-pandemic levels. The pandemic’s effect on health-care workers must be contributing to this decline in volume, but it can’t account for all of it. Most patients can still snag a specialist appointment within two or three weeks, according to McKinsey’s data.

It’s possible that many long-haulers have simply given up on getting medical care, because they’ve understandably concluded that treatments don’t exist or that doctors won’t believe they’re sick. (The scarcity of clinics dedicated to patients with long COVID could also be a problem.) The U.K.’s Office for National Statistics has been performing one of the world’s largest long-COVID surveys, in an effort to measure the full extent of this behind-the-scenes suffering. The study shows that, as of the beginning of May, 3 percent of that country’s residents identify as having long COVID, broadly defined as “still experiencing [any] symptoms” more than four weeks after first getting sick. (Eighty percent of the U.K. population is estimated to have been infected with the coronavirus at least once.) About two-thirds of this group—amounting to more than 1 million people—say that the condition affects their ability to perform day-to-day activities. Among the survey’s most-cited chronic symptoms are weakness, shortness of breath, difficulty concentrating, muscle aches, and headaches.

In its focus on persistent symptoms, the U.K. survey may be leaving out other, more insidious consequences of COVID. A CDC analysis, published last month, examined the medical records from hundreds of thousands of adult COVID patients, and concluded that at least one in five might experience post-illness complications. Some of these were of the familiar types (trouble breathing, muscle pain); others were of the ticking-time-bomb variety, including blood clots, kidney failure, and heart attacks. This study’s methods have been harshly criticized—people who have long COVID “deserve better, much better,” Walid Gellad, a professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh, told me—and the one-in-five statistic could be way too high. But if the CDC’s results are correct in substance—if various mortal dangers do increase by a significant degree after COVID—then the effects of these should also be detectable at the population level. Comparisons between individual study results and overall disease burden offer a reality check for extreme findings, Jason Abaluck, an economist and a health-policy expert at Yale, told me. “They allow you to put bounds on things.”

Where does that leave us with long COVID? The majority of Americans have already encountered the virus, many more than once. The CDC suggests that these people will, on average, experience about a 50 percent increase in their respective risks of blood clots, kidney failure, and heart attacks, as well as diabetes and asthma. Comprehensive national disease estimates will take years to compile, but provisional rates of death from heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease haven’t really budged since 2019, and the NHIS survey has shown no increase in the number of Americans with high blood pressure or asthma.

In short, here’s what we can say right now: Disability rates might be rising, but only by a little bit; the health-care system seems to be coping; deaths from post-COVID complications aren’t mounting; and the labor force is holding up. Long COVID, in other words, isn’t yet standing out amid the pandemic’s other social upheavals.

Liza Fisher has long COVID, and she shows up in the data. The 38-year-old former flight attendant and yoga instructor from Houston became ill with COVID in June 2020. Her infection led to months of hospitalizations, procedures, and rehabilitation. She now requires a team of medical specialists, and she remains severely limited in her daily activities because of neurological symptoms, fatigue, and allergic reactions. Fisher went on medical leave from work after her symptoms began, and she never returned. In December 2020, she applied for disability benefits from the Social Security Administration, and was granted them about six months later.

“Government numbers aren’t accurate, and may never be accurate,” Fisher told me. She knows of long-haulers who have applied for disability programs under better-established diagnoses, for instance, because they believed that citing long COVID wouldn’t grant them access. And she said that when national metrics don’t reflect the everyday reality of the long-COVID community, advocating for research, treatment, and support services becomes more difficult.

Frank Ziegler also has long COVID, but he hasn’t quit his job, nor has he put in a claim for any benefits. A 58-year-old lawyer from Nashville, Tennessee, Ziegler developed a mild case of COVID in January 2021. The nasal congestion he experienced was so unremarkable that he assumed at first he had a simple sinus infection. But in the course of his recovery, something about Ziegler’s appetite changed—seemingly for good. Foods he had previously loved became strangely unappetizing; he lost a significant amount of weight. Then he started noticing hand tremors, trouble breathing, and cognitive issues. A battery of medical tests came back essentially normal, but Ziegler still doesn’t feel as well as he did before catching the virus. His life has changed, but that difference might not be reflected on any government graph. “The square pegs of long-COVID patients are never going to fit into the round holes of conventional testing,” he told me.

The mix of symptoms and experiences that define long COVID suggests that no single measure, or group of measures, can illustrate the suffering of long-haulers in aggregate. A “mass disabling event” is not playing out in the data we have. That could change in the months and years to come, or else it might indicate that we’re in another kind of moment, one that leaves tens of millions of Americans feeling somewhat worse off than they were before, not so sick that they can’t hold down a job or need medical attention, but also not quite back to baseline. Call it a “mass deterioration event.”

“There are a significant number of people that can’t simply move on,” Ziegler told me. “Many of them have no idea why they are feeling the way they do, and they have not been able to get any relief.” That form of epidemic—one that degrades quality of life, incrementally, for millions—is likely unfolding, even as a much smaller group of patients, including Fisher, see their lives utterly transformed by chronic illness. We don’t know how bad the long-COVID crisis will get, but for many, there’s no turning back.