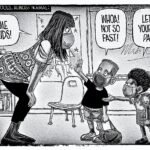

Over the weekend I was contacted by the mother of a girl, pre-pubescent, who had socially transitioned at school without parental knowledge. The girl (let’s call her Samantha) had asked teachers to call her a boy’s name (let’s say Johnny) and use he/him pronouns for her. Her teacher complied, announcing to the entire class that Johnny was now a boy and could use the boys toilet and play on boys’ sports teams. The mother was only made aware of this when one of Samantha’s friends came to the house, asking, “Is Johnny in? He said to call for him to go to town”.

You would expect the Government to crack down on this sudden and potentially catastrophic reduction in parental authority. Yet the draft government guidance on social transitioning in schools does no such thing. While it sings the right tune – stating there is “no general duty” for schools to allow social transitioning, and that parents should not be excluded from decision-making – the guidance is non-statutory and could potentially be ignored.

Teachers’ hands must be forced on this critical matter, because the rate at which children are being socially transitioned has become overwhelming. Indeed, The Telegraph recently published an analysis of more than 600 school equalities and trans policies, finding that up to three-quarters misrepresent laws protecting sex and gender, with some implementing rules such as letting boys use girls’ toilets and changing rooms if they say they are a girl. One trust, which included a number of Church of England primary schools, had even advised teachers to assist girls using breast binders while on school trips.

It’s no surprise, then, that many parents feel they have lost their voice in this process. An unfortunate minority must feel that they have lost their child too. On the most critical of elements in Samantha’s life, her mother was excluded. But it is important to recognise that there are still ways to end this. If the Government is too afraid to do anything, then it ought to be put to the people in a referendum on transgender ideology – and in particular on social transitioning in schools.

This referendum should be clear in its aims and objectives, and state boldly that the question is not about transgender adults or sexual orientation. Adults can be and do whatever they want. But claiming to be – and being treated as – the opposite sex in school is an altogether different matter. Unless children desist early on, transitioning can involve puberty blockers and surgery – the effects of which might well be irreversible.

Critics of such a referendum will point to Hungary, with its far-Right government. In addition to asking whether sex reassignment therapy should be promoted to children, the Hungarian referendum included questions on whether or not children should be given information about same-sex relationships. This was, of course, totally inappropriate.

Our referendum would have to be reasonable. It must avoid falling into the trap of genuine transphobia or homophobia, and focus on the rights of parents to regulate their children’s behaviour. My hope is that such a referendum would form the basis of a new law for parents, that allows them to take back control.